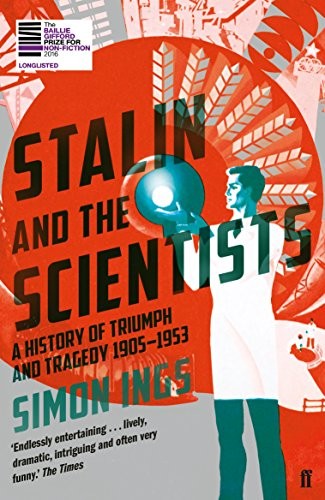

Sally Strange reviewed Stalin and the Scientists by Simon Ings

What is the role of science and scientists in governance?

That's the question at the heart of this book. Using the early history of the USSR is a great way to explore it, because from the beginning, the Bolsheviks styled themselves as scientific leaders in the process of creating a new, rational society untouched by the superstition of the old regime.

Of course, their hubris and ignorance led them to disastrously sideline, ignore, imprison, murder, and even enslave a great many scientists whose opinions were at odds with the official narrative. For instance, the author recounts how Stalin's collective denouncements of traitors to the revolution actually had long-standing roots in village church life, that such denunciations and collective punishment served as a way to protect the collective survival of the residents, who would be unable to grow enough food if too many people took off for, say, work in a factory in a nearby city. Another famous example is that …

That's the question at the heart of this book. Using the early history of the USSR is a great way to explore it, because from the beginning, the Bolsheviks styled themselves as scientific leaders in the process of creating a new, rational society untouched by the superstition of the old regime.

Of course, their hubris and ignorance led them to disastrously sideline, ignore, imprison, murder, and even enslave a great many scientists whose opinions were at odds with the official narrative. For instance, the author recounts how Stalin's collective denouncements of traitors to the revolution actually had long-standing roots in village church life, that such denunciations and collective punishment served as a way to protect the collective survival of the residents, who would be unable to grow enough food if too many people took off for, say, work in a factory in a nearby city. Another famous example is that of Trofim Lysenko, whose "barefoot scientist" celebrity status as a man who started as a peasant and achieved great heights of professional acclaim within the USSR despite his lack of scientific acumen and joke status in the rest of the world owed a great deal to the fact that Stalin fancied himself an amateur agronomist and dreamed of growing lemon trees in Moscow.

The book is a bit hard to follow at times, since it proceeds in a more or less linear fashion, but bounces forward and then back again as it tackles different disciplines and groups of scientists' encounters with the Soviet regime. But it's worth it to stick with it till the end.