This book is a collection of five novels and four short stories, as well as an essay and introductions to each of those novels, set in Le Guin's Hainish universe. Each novel contains all the information about the universe necessary to understand that novel, though taken together they reveal a more complex picture than any one alone. The gist is that millions of years ago, the people of a planet called Hain or Davenant seeded various worlds with human colonists. (Though most of these worlds had no previous inhabitants, it is mentioned in one story that hominid life arose independantly on Earth; humans, however, are descended from Hainish settlers.) This serves as a vehicle for exploring humanity in various contexts and situations which otherwise do not exist in real life, as the League of All Worlds - or the Ekumen, in the later novels - started by Hain seeks to re-establish contact with its former colonies, not to rule them, but to welcome them into a free and equal relationship. This is hampered by the limitations of physics, which does not allow massive objects to travel at or above the speed of light; but it is mitigated by the time dilation of near-light-speed travel, which allows humans to survive these voyages, and in some stories a device called an ansible, which uses quantum entaglement to instantaneously transmit messages over arbitrary distances.

This collection begins with Le Guin's first published novel, Rocannon's World. It, however, begins a theme of the collection: the problematic milieu in which it originated; namely, the US for about a decade from the early 1960's to the early 1970's. The most glaring example of this is the way women are spoken of - weak, emotional, and the like. Each novel in this collection seems to have this common flaw. Planet of Exile brings it to the fore by having a female point-of-view character. Le Guin addresses this particular critique in several of the essays and forewards included with the collection, notably the "Introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness" and the excellent "Is Gender Necessary? Redux," a running response/critique of an earlier essay with the same name minus "Redux." There is also a short story, "Vaster Than Empires and More Slow," which includes a problematic description of autism. This particular issue isn't addressed in the extra texts, but one might safely assume it results from a similar lack of knowledge and experience. Taken as a whole, this collection shows a burgeoning author growing both as a writer and a person. Even its flaws may be forgiven for the fact that the author herself recognizes and, in the later works, critiques them. In this way, she functions as a mirror for the world in which she was living, which was awakening to its biases and harms in ways it hadn't before. We must be grateful that she and so many others were doing this work so that we may sit in our current time and see the flaws so clearly.

Continuing the discussion of her growth in this collection, Le Guin's defining characteristic for me has always been her ability to evoke what I can only describe as a meditative state. While the first two novels lack this completely, there was a moment near the end of City of Illusions which evoked this sense in me. The Left Hand of Darkness, which I was reading for the second time, had not evoked this in me before; this time, it did. And of course, The Dispossessed remains one of her greatest works.

Now to the stories themselves.

Rocannon's World - in this edition prepended by the short story "The Necklace," a prequel to the original novel - follows a servant of the League of Known Worlds who goes to an unnamed planet to explore and name it, and to bring it into said League. He is drawn by the necklace, taken from the world by its first League visitors and recovered by one of its nobility in the short story. Once he arrives, his ship is destroyed by a mysterious enemy; the rest of the story follows his quest to find the source of the attack and alert the rest of the League to the potential threat. Overall, the story is classic '60's sci-fi mixed with fantasy, with a heroic adventurer galavanting about, discovering amazing things, overcoming tremendous hardships, and having wonderous experiences. It's a fine if clearly dated book.

Planet of Exile is set on a different world. Here, a colony of abandoned League-affiliated Alterrans coexists - or, more precisely, exist beside and apart from - the native people of the planet. The plot follows the harrowing preparations for the decade-plus-long winter of this world, during which a tribe of nomads travels down from the north, raiding and destroying along the way. It is not precisely a traditional science-fiction story, and reveals a bit more about the nature of the League and the broader Hainish universe. Although I felt hesitant at first because of the overt misogyny of the native society, even of a point-of-view character who is a woman, I regardless felt myself deeply engaged with the story and pleased with its outcome.

City of Illusions is set on Earth. However, this is not the Earth we know, nor the one the League knew. Indeed, as far as we can tell, the League no longer exists in this novel. It follows a man whose memory has been lost or taken as he travels across what was once the United States on a quest to unlock his memories, his past, and possibly the future of the planet. I personally found the first 3/4ths or so of the book slow, sometimes interesting but often boring, with relatively little in the way of redemption. However, near the end, things change completely, for the protagonist as well as for the reader; here Le Guin demonstrates for the first time in this collection a glimpse of her power as a writer, a storyteller - or as she might put it, as a liar. The first part of the book becomes worth it as various mysteries are revealed, aspects of the plot are twisted, and entirely new information is revealed in the closing chapters. I left a book I expected to dislike with only appreciation for what it wrought.

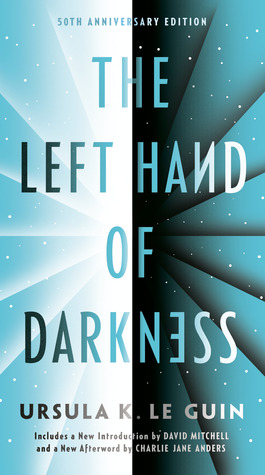

The Left Hand of Darkness is a classic of science-fiction, and probably one of Le Guin's most famous works. It follows the First Mobile - a servant of the Ekumen of Worlds, apparently a successor to the League - as he attempts to convince first a feudal monarchy then an autocratic bureaucracy to join the Ekumen. The reason this novel is so famous is because the people of this world, which calls itself Gethen and is called Winter elsewhere, are naturally "ambisexual," to borrow the novel's term. That is, they are capable of expressing either traditionally biologically male or traditionally biologically female sexual characteristics during their period of sexual activity. Yet, nothing I've mentioned so far is really what the book is about. I won't ruin the discovery of its true topic by trying to put it into words here, but I will say that it is well worth reading, despite its dated understanding of sex and gender. As for its dated understanding of sexuality, "Coming of Age in Karhide," one of two short stories in the collection set on Gethen, help alleviate it significantly - though do be warned it discusses sexuality among people who, on Earth, are considered minors, in a society with very few of our own sexual taboos. All of that is to say, read it. If I tried to explain why, I would only fail to convey its significance. (Also read the "Introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness" in the appendix; though wait until after reading the novel if you haven't read it before.)

Finally we come to what I regularly describe as "the most important/influential book I've ever read:" The Dispossessed. Unfortunately given the misleading subtitle "An Ambiguous Utopia" by its publisher, this book is not about a utopia. What it is about is a physicist from an anarchist society who struggles against the restrictions of his home moon going down to the planet his ancestors fled and learning something of the restrictions of a capitalist society. I won't describe the story any more than that because there's little more to it. As one of the greatest novels ever written, it's not about anything particularly special. It's just about people, some of whom happen to have built a society without governments - though not fully, as is the anarchist goal, without hierarchy. The first time I read the book, the lesson I took away was that revolution is possible, but that that revolution will need to be continually revolving, and will likely never end. This second reading, I was much more interested in how utterly human the anarchist characters feel, and how utterly alien the capitalist ones feel. I don't have much more to say on the topic, except that this feeling is highlighted by the companion short story, "The Day Before the Revolution." It shows the founding thinker of these anarchists, a woman named Odo, and what I believe is meant to be understood as her final day of life. It is an utterly mundane and human story.

There is one short story not accompanying one of the novels, "Vaster Than Empires and More Slow." It's a problematic if fascinating piece of speculative fiction. What it speculates on is two-fold: what if a crew of people with mental illnesses were loaded into a near-light-speed ship and sent hundreds of lightyears away from their lives to explore entirely uninhabited planets? and something I can't reveal as it is a key plot twist. This story wound up being quite moving and poignant, but is marred by a primitive understanding of psychology and mental illness. Like all of Le Guin's works from City of Illusions on, however, it demonstrates a very deep understanding of humans and of humanity.